Batten Down the Hatches, And Make a Game-Changing Move?

The Need and Opportunity for Value-Delivery Innovation During the Downturn

By Michael J. Lanning and Helmut Meixner

While not easy in a furious storm like this severe economic downturn, we urge that businesses and their leaders summon the will and focus to not only batten down the hatches and protect the ship (and its near-term cash-flow). They should also quickly and decisively replot the ship’s course, based on a new, penetrating scan of surrounding seas.

Most businesses have reacted to the downturn by cutting costs, and they recognize that customers (business and consumer) will be much more price sensitive for the duration of the recession. Some businesses will also act more aggressively, and continue investing in future growth. However, most will assume that once the recession ends, their markets will behave much as they did prior to the downturn. We believe that the emerging winners, in contrast, will assume that the downturn is likely creating major new opportunities and threats.

In fact, we believe most businesses should immediately, and fundamentally, rethink their strategies, based on new, deep imaginative study of their markets. Such creative exploration would reveal that, in many markets, the recession is catalyzing major, nonobvious, lasting changes in the behaviors and priorities of customers (business and/or consumer), competitors, regulators, and others. Using insights into these changes, most businesses then could and should boldly make game-changing moves, delivering innovative new value propositions, in new ways, that capitalize on the current turmoil to generate breakthrough profitable growth as the economy recovers.

Nvidia – Example of Forward-Looking Insight and Innovation

Winners address the fundamental problem in a recession – how to regenerate demand. To do so, they must discover forward-looking insights – creatively inferring new experiences customers likely will value, not what they thought they wanted last year. Based on such insights, businesses must then develop value-delivery innovations that generate new excitement, enthusiasm and robust demand.

A current example may be Nvidia, chip-making competitor to Intel and Advanced Micro Devices. Nvidia intends to increase R&D spending, while most others are cutting back and despite a 40-50% revenue drop in late 2008.(1) Based on Nvidia’s study of end-users, CEO JH Huang foresees a new PC environment emerging from the downturn, a market with dramatically lower baseline hardware prices, differentiated by “size, battery life, and video performance.” Nvidia is “prepared for that outcome,” Huang says.

As evidence of such a shift in end-user preferences, he points to the emergence of netbooks, low-end portables designed for wireless communication and web access. They are smaller, lighter, and depend on web-based applications. He “predicts consumers will discover they don’t need hardware with a high-end [Intel] microprocessor…Instead… they’ll get more for less by allocating their dollars toward Nvidia chips that are more efficient for chores such as watching videos.” Huang asks, “What is the soul of the new PC?” He is betting that Nvidia has the answer.

Options Businesses Face in a Severe Downturn

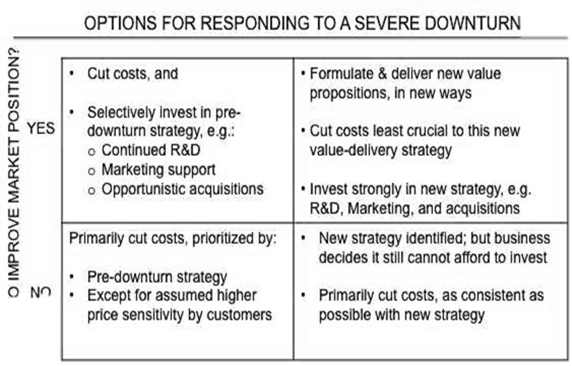

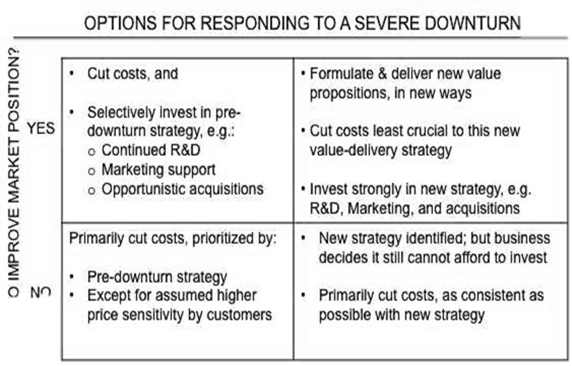

The matrix below depicts the options – whether to first rethink strategy, based on an exploration of market changes, and then to identify and make game-changing moves. Many will gravitate to the lower-left quadrant, just battening down the hatches, while a few move into the upper-left, trying to strengthen market position. Both these quadrants assume that the pre-downturn rules in the market will hold up when the recession ends. The biggest winners, however, will move to the right, especially upper-right, exploring markets and rethinking strategy, then pursuing the biggest game-changing opportunities.

Why Deep Study of Downturn-Catalyzed Market Changes is so Crucial

Market changes need deep and careful study because some changes and their implications are not at all obvious, and are not revealed by a simple extrapolation from trends prior-to and during a downturn. For example, consider the long economic stagnation of Japan’s ‘lost decade’ – about 1993 to 2001 – which resulted in some very interesting but nonobvious long-term changes in consumer behavior.

After little-to-no growth for nearly a decade, the Japanese economy recovered well (until 2008). Yet, long after the recovery began, some surprising behaviors that had developed during the stagnant years persisted. (2)

During the booming years prior to the stagnation, Japanese had felt wealthy, and many exhibited American-style conspicuous-consumption – wearing foreign fashion, drinking Scotch Whiskey, driving luxury cars. Sales of such items dropped sharply during the lost decade, but by 2007, after six years of recovery, volumes were still down – e.g. Whiskey at -80% since its 1980s peak, and auto volumes at -50% versus 1990. “I’m not interested in big spending,” said one college student. “I just want a humble life.”

And remarkably, a poll by news daily Nikkei found that the percentage of men in their 20s who said they wanted a car had dropped from 48% in 2000, to 25% last year.

This reduced desire for a car corresponds to many Japanese spending less time driving cars and more time on public transportation, in long commutes. And that behavior in turn actually feeds into another phenomenon – a strong growing demand for wireless access to broadband-oriented information and entertainment.

Starting about 2000, about seven years ahead of the US, Japan rolled out ‘Third Generation’ (3G) wireless telecomm technology,(3) which the US only began seeing in 2007. Advanced 3G is now fast enough to support Video On Demand (VOD) technology (where consumers can view any movie, etc., on demand, anytime) on a cell phone. Japan now leads the world in adoption of VOD. (4) And who is watching VOD on their cell phones? Those Japanese commuters. Sitting on a train for an hour or more, they highly value a quality entertainment experience on their cell phones, and they’re getting it.

This unfolding scenario could only be anticipated by insightful understanding of the changing behaviors and attitudes of these consumers. Extrapolating from trends prior to the downturn and assuming a return to ‘normalcy’ would have missed this train.

So we urge businesses to adopt a realistic, systematic methodology for creative marketexploration and strategy reformulation. We believe such a methodology must include indepth engagement with customers (business and/or consumer), and other analysis of shifting behaviors of customers, competitors, regulators. This exploration must discover forward-looking insights, translated into value-delivery innovations that can generate major new demand. This is a methodology for those willing to go beyond battening down the hatches to also take their fate in their hands and make a truly game-changing move.

Historical Support for Making Game-Changing Moves in a Downturn

In every serious recession, most companies are reactive, necessarily cutting costs. Yet a small number of players also look actively for big opportunities created by the turmoil and, though battered near-term by the downturn, they make serious game-changing moves that often achieve much stronger market position by the end of the recession.

Japan, South Korea, and some other Asian export economies are known for taking a long view, often seeing downturns as share-gain opportunities. For example, in the 1990-91 recession, with automotive sales and profits down sharply, Toyota and Honda invested heavily in their innovative new luxury models, Lexus and Acura. This move did not feature their lower-cost models, and some observers thought the luxury-emphasis an odd risk in a recession. However, Toyota and Honda bet that luxury-car motorists were ripe for a better value proposition than Mercedes, Cadillac, or Lincoln; Lexus and Acura offered equal comfort, performance, and luxury-features, a superior, more convenient approach to dealer-servicing, and a long-standing reputation for superior reliability.

Detroit’s (then) Big Three responded to the recession in customary fashion, cutting newmodel development budgets, squeezing suppliers, and complaining about unfair Japanese trade practices. Lexus and Acura were big hits and soon took leadership of the luxury sedan segment. In 1990-91, Japanese companies gained over 4 share points of the US market, to over 30% for the first time, mostly attributed to success of the new luxury models. Japanese makers, according to the NY Times in late 1991, weren’t surprised, saying Detroit was ‘unprepared’ for the recession. A top Honda executive noted:

“There is still a basic, fundamental difference between Japanese and U.S. manufacturers in a time of downturn. The Japanese bring out new models and try to revitalize their lines. They use a recession to rebuild their capacity. The Big Three tend to delay introductions or cut the budget to develop new models. They tend to wait.” (5)

Japanese executives may sound a bit more humble these days, but this aggressive approach to downturns seems to characterize much Japanese business thinking. In today’s downturn, Yokohama Rubber, in the hard-hit tire industry, announced recently(6) that they will move ahead with plans to build a new plant in Russia, and a deal with Continental to produce Yokohama tires in Brazil, despite a $79 million loss for Yokohama in 2008. And Kao, the Japanese consumer products company, recently announced(7) plans to invest $8 million in a new US headquarters.

Historically, many other winning companies have taken a similar approach. In the early 1870s, despite a recession following the bursting of the post-Civil-War speculative bubble, John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie moved aggressively to take advantage of new technology and weakened competitors in the young oil and steel industries.

Following the bursting of another bubble in 1893, based on railroad bonds, the ‘Long Depression’ of 1893-97 set in. But while making fortunes investing in expansion of railroads was largely finished, as Richard Rumelt points out, (8) the end of the railroadbuilding boom marked the emergence of a new economy based on sophisticated consumer goods. Hershey’s Chocolates, among others, saw early growth in this period. Similarly, the era of electricity was dawning, and during this period, despite the Long Depression, General Electric and Westinghouse Electric achieved their initial growth.

In the Great Depression of the 1930s, as Tom Nicholas points out,(9) patent applications dropped, as corporations generally preferred to ‘wait and see’ before proceeding with R&D investments. But several notable players did not wait. DuPont invested aggressively in its 1930 discovery of neoprene, finally commercializing it in 1937, after which it became an enormously successful innovation, the first mass-produced synthetic rubber compound. Two early icons of technological innovation, Hewlett-Packard and Polaroid, were started in the 1930s. RCA, moving beyond radio technology, invested heavily in early TV innovations, with major later payoff.

The Problem is Demand, the Solution is Value-Delivery Innovation

It is clearly risky to go beyond cost cutting and actually invest during a recession, without a clear and updated vision of what innovations could generate major new demand in the changing market. Toyota and Honda, GE and Westinghouse, DuPont, HP, Polaroid, RCA – these players seem to have had a clear vision of a changing market where they could generate new demand by delivering value propositions innovatively.

The western, developed nations and much of the global economy has enjoyed a long period of remarkable growth in the post World War II era, though punctuated with numerous recessionary setbacks. Three of the key factors driving much of that growth have been: innovation in value-delivery to customers; the opening of markets; and, especially in the past 20 years, the expansion of leverage through cheap credit. The latter two factors, however, have been diminished by the current, very steep and sudden downturn. We strongly suspect that with this recession, innovation will prove to be more crucial than ever in regenerating new demand.

Innovative value-delivery-to-customers means significant new improvements in the beneficial experiences delivered to customers and/or in the cost of their delivery (usually resulting in lower costs for customers). These value-delivery innovations are facilitated by breakthroughs in product-performance and technology, as well as in creative new services, ways of providing information, forms of product distribution, means of communication to customers, etc. Such innovation has always been a central engine of business growth, perhaps of accelerating importance over the past 60 years or so.

The steady global opening of markets has been a second important factor in spurring growth, albeit entailing its own economic, social, and political complications and tradeoffs. This opening includes widespread liberalization of economies and markets, deregulation, globalization, and increased international trade. However, this factor will likely be under renewed political pressures as the recession spurs protectionist sentiment (as seen in the buy-American provision of the recent US stimulus legislation).

A third factor that helped fuel much growth since the 1980s, particularly important in the key North American region, has been the expansion of leverage based on cheap debt. As a result of the steep downturn this third factor is not likely to return when the recession ends. As Lowell Bryant and Diana Farrell said in a December article, “For many companies the high returns and rapid growth of recent years rested on cheap credit, so deleveraging means that expectations of baseline profitability and economic growth…must…be seriously recalibrated.” (10)

Growth in demand, therefore, will be more dependent on innovation. Businesses should therefore now focus more on innovation, not less, than in normal times.

Emerging Examples of Investing in Innovation in the face of Recession

Already in the current downturn, a few signs are evident of companies investing in innovation, reflecting changes they see being spurred by the steep recession. Cisco’s John Chambers recently announced that Cisco has sharply cut travel expenses (from $7900 per employee to a rate of $3400) and, “That will not come back” because the company is successfully transitioning to much greater use of video conferencing, web meetings, and collaborative software, in place of airlines and autos. (11) Of course, Cisco sells these systems and the announcement is meant to urge other companies to follow suit. Chambers has been known to argue that downturns are growth opportunities for new technologies and solutions; Cisco seems to be betting now that the economic turmoil will catalyze a long-term, not temporary, shift toward long-distance meeting and collaboration in place of business travel.

A senior executive of Korean electronics giant LG signaled in January (as reported by CNNmoney.com) that LG will continue investing in value-delivery innovation, even if revenue growth proves difficult:

“Even though the [flat-screen TV] market has a ‘downgrade’ trend for the high-income segment, there is still a premium market and they need to differentiate innovative products, technology wise… We are going to continue to develop such a product so that we can keep LG as a premium brand and we can enjoy that market…

(12) “Even though we have a recession now, like everybody, we do not want to reduce our marketing spending and we want to invest more money on R&D and customer service and eco-friendly and environmental issues…It is a hard decision because revenue could be reduced because of the recession and profit will reduce because of competition. But we want to invest for our future.” He also said LG may expand its retail footprint by selling its products through mass merchandise clubs…

The historical and contemporary examples cited here illustrate investing aggressively in innovations that can generate new demand, despite the difficult conditions of a recession. But many businesses will reject such a mindset, without much thought, confident that now is not the time for innovation, but the time for single-minded cost cutting. However, simply making marginal cost reductions may help the short term protection of cash flow, but won’t generate significant new demand. Only through innovations that deliver new valuable, even captivating experiences – new benefits or cost savings for customers – can new demand be generated in the face of widespread reluctance to spend money.

The reader no doubt sees other examples emerging in various markets.

After Rethinking a Business Strategy, Invest in New Innovation

Of course, even looking hard, not every business will find opportunities for value-delivery innovation that can generate new demand during and coming out of the downturn. In objectively and creatively rethinking strategy, a business must be prepared to draw and accept one of three broad conclusions:

- Despite economic turmoil, the business still delivers good value propositions, but there is no opportunity to strengthen market position; as revenue is down, costs should be cut, guided by the priorities of delivering the current value propositions

- Or, there is major opportunity to strengthen market position during and coming out of the downturn. A fundamentally stronger market position may mean either:

- Winning a higher profitable share of an existing market where the business competes; could include moving from ‘also-ran’ to market leadership;

- Or, entering and winning a leading share in a market new for the business;

- Or, generating profitable new consumption by an entire market, by leading end-users to adopt new/increased usage, while holding or winning strong market share; could be a current market for the business, or a whole new market, possibly a ‘blue ocean’ (low-competitive-intensity) opportunity

- Or, the market exploration reveals that there is no winning value proposition which the business could profitably deliver in the foreseeable future. The business is no longer viable and should be liquidated as soon as practically possible.

Without carefully rethinking the strategy of a business, most managers will implicitly adopt conclusion #1 above, though we believe it often the least realistic and appropriate.

While conclusion #3 is an unhappy one, it is better reached sooner than later, as the value of such a business will likely deteriorate steadily and perhaps increasingly during such a severe downturn. A thorough and imaginative exploration of current changes in the market is the surest, most objective backdrop against which to quickly discover that a business can no longer hope to deliver any winning value proposition.

In the case of the relatively realistic yet very encouraging outcome #2 above, pursuing a much stronger market position (whether a leading market share or total-market growth) will almost always require at least some adjustment if not major change in the value propositions delivered and how they are delivered (provided and communicated).

In either case, the evidence is clear that once the appropriate changes have been determined, businesses that win during and coming out of recessions tend to increase investment in value-delivery innovation, including both R&D and marketing. Some of the historical examples cited earlier support this conclusion, which seems to be behind much academic and consulting advice to be aggressive in a downturn. The data on spending during recessions also seems to support this conclusion.

For example, Bain & Company studied over 700 firms’ performance during 6 years that included the 1990-91 recession. (13) During that recession, about 2/5 of all companies either moved from the bottom quartile to the top, or fell from top to the bottom, twice as many such leaps as occurred before or after the recession. “Many managers tolerate subpar results… believing [they] will accelerate past competitors once the economy recovers. This rarely happens. More than two thirds…that made major gains [in the 6 years] did so during the recession, not before or after…The impact of exercising [opportunities] is much higher during a recession, when many competitors are either distracted or hibernating.”

Another study, (14) from 2002, looked at 1000 mostly industrial firms from 1982-99, including two recessions, examining characteristics of those that either stayed in or moved into the top quartile of performance in their industries. Not too surprisingly, the successful challengers were more likely to make acquisitions during a recession. In addition, while most companies cut expenses, the successful challengers spent +14% more on SG&A during the recessions, than those who lost leadership. In contrast, successful leaders spent -14% less on SG&A than their less successful peers, during nonrecessionary times. Advertising spending showed a similar pattern. In R&D, successful leaders spent +8% more than less successful peers even during non-recessionary periods, but the successful challengers outspent the less successful by +22% during the recessions.

In addition to investment in technology and marketing, businesses armed with an innovative new strategy reflecting changes caused by the downturn may also wisely invest in various supporting assets. Competitors, complementors, new technologies, manufacturing assets, talent, and other assets that may fit the new strategy, may be available at depressed prices in the recessionary environment.

Refining Value-Delivery Strategy to Reflect Customers’ current Focus

The broader economy must inevitably be impacting behaviors and priorities among businesses and consumers. Therefore, even if current value propositions are about right, it is likely that significant adjustments to those value propositions and/or how they are delivered (provided and communicated), are necessary for optimal success.

Clearly customers are much more concerned about costs than a few months ago. It seems likely appropriate to fine tune value propositions or how they are delivered, to better meet the needs of their customers in an economic downturn. Such refinements should be about helping customers reduce expenses, or see and receive more value. For example:

- Help industrial customers achieve lower total costs by running at lower speeds. Since most customers have idle capacity, they could run their lines at slower speed. Maybe they could save money by using less power, etc. Sometimes, running slower results in better quality and/or fewer rejects.

- Perhaps use lower cost and lower quality materials in making our product, but converted into equal/better quality end results in the customers’ operation, by running longer on the their lines, again recognizing the spare capacity they may have

- Use customers’ facilities and spare people to do more processing in-house, allowing less preparation/pre-work by us, saving total cost, shared between customer and us

- Communicate superior value due to total cost, despite higher price, a common emphasis of consumer products in downturns; e.g., ‘Gillette blades last longer, so cost less per shave vs other blades,’ or ‘Bounty paper towels clean up spills with fewer sheets than cheaper paper towels,’ etc.

Discovering Major Lasting Changes and the Greatest Innovation Opportunities

Perhaps most crucial to emerging from the downturn as a long-term winner, businesses need to devote attention now to imaginatively and deeply studying changes in their markets because some of those changes will likely be major, long lasting, and yet not very obvious to spot or easy to predict. Discovering and understanding these changes is not likely without a fresh, deep exploration of current/ potential customers and other key players in the market now.

During the 1930s, behavioral changes and accompanying markets were stimulated by the changes caused by the Depression, and further by new technologies. Entertainment soared in popularity, the movies providing an affordable escape, and became a key US industry. And people were on the move, on the road, so the motel became very popular and then a lasting fixture of the American scene. Without waiting for 1950, one could have foreseen some of this by deeply exploring the changing habits and mindset of the US consumer by the early-to-mid 1930s.

Today, Cisco’s bet (noted earlier) on the replacement of much business travel with teleconferencing and related technologies, is another example. Here, Cisco is trying to innovatively capitalize on behavioral changes that are spurred by the current intensely cost-conscious environment but which may have potential for long-term shifts.

In the US, residential housing will eventually recover, but perhaps not in the same form of recent years. One could speculate that many homeowners may come out of the recession disillusioned by the guaranteed wealth-building formula they were taught was a home. And with recovery, rising oil prices may return as well, making long commutes expensive. Are some segments of homeowners becoming more interested in ‘sustainable living?’ Conceivably, might these and other changes combine to start changing where and in what kinds of structure homeowners are interested in living? Deeply studying their evolving attitudes could reveal much new insight to businesses in this changing market.

Businesses should be studying their markets to learn, ‘what changes are percolating in the lives and businesses of customers and other key players, stirred by the economic turmoil? What implications do those changes have for potential innovations in value delivery that our business might introduce?’

Albeit not usually easy, the biggest opportunities for value-delivery innovation often involve restructuring how a business and its customers operate. This principle applies strongly to both business-customers and consumers. The tumultuous environment may facilitate such restructuring moves that can redraw the competitive landscape, e.g.:

- Are there changes in business-customers’ operations that would allow the business to convince customers that now is an opportune time to outsource various processes to that business? Bundling the traditional product with those outsourced processes could redefine the value delivery systems of both the business and its customers.

- Are there new opportunities emerging for the business to help customers enter new markets, or to compete more effectively in current markets?

- Is the downturn undermining the value distributors or other intermediaries deliver, between a business and end-users? Do such changes create opportunity to initiate more direct relationships to end-users?

- Though shell-shocked, might the construction industry be riper than ever for major supply-chain restructuring, such as expanded use of pre-fab materials?

We don’t mean to propose that businesses select from neat recipes of specific solutions, in a downturn, such as some discussed here illustratively. Nor should businesses imitate any of the historical and contemporary examples of innovators cited in this article. The point is that businesses should not assume they already know what strategy is right for markets undergoing the hard to predict transformations brought about by a severe and possibly rather lengthy downturn. Instead, they should invest in deeply immersing themselves in the changing businesses and lives of customers, to understand and interpret their changing behaviors and priorities, while also analyzing the behaviors of other key players in the market, including intermediaries, competitors, and regulators.

A Realistic, Market-Focused Methodology for Rethinking Strategy in the Downturn

We urge that a business follow a two-part methodology for rethinking strategy in light of the fast-changing environment. The business should first deeply and creatively explore its markets to identify major lasting, but often non-obvious, changes unfolding now in the behaviors and priorities of key players. Based on insights from that exploration, the business should then reformulate the winning value propositions, and redesign how to best deliver (i.e. provide and communicate) them.

The market-exploration phase consists of identifying and analyzing the changes happening in key elements of the market, including in:

- The behaviors, priorities, and values of current and potential end-users and other customer groups – what they will likely want and be willing to pay for it

- The structure and dynamics of the relevant value-delivery chains, including changing roles for various intermediaries, complementors, and others

- Competitor behaviors, objectives, capacities, and limitations – which existing or potential competitors are likely vulnerable, and which are likely to be aggressive? This analysis should include obvious current competitors, as well as potential threats from different technologies or other regions (e.g. China, Japan, Europe, etc.)

- Regulators’ and other governmental bodies’ priorities, and thus the incentives, support, and constraints they may bring to the market

Some businesses will be inclined to skip the first two items, analyzing competitors and maybe regulators, and focusing most attention on cost cutting. This may seem no time for ‘academic research and segmentation analyses.’ However, we would argue that now is an especially crucial time, not for academic studies, but to engage deeply with current/ potential customers and perhaps a few others in your chain.

Essential to our suggested approach is studying what current and potential customers are actually doing today, then creatively inferring what experiences those customers will likely therefore value in the near future. This approach fundamentally differs from many methods that rely on having customers tell us what they think they want. It is also forward looking – not a discovery of what customers used to value just before the economy melted down. And this methodology is actionable, not an elaborate exercise in observing and characterizing groups by academically interesting categories, without surfacing concrete hypotheses for possible value-delivery innovations.

Consumers are not difficult to engage in detailed discussion of what they are doing and thinking. Plenty of money can be wasted by over-intellectualizing this task. But managers can engage directly with consumers, especially in individual in-depth interviews, often useful to conduct at home or otherwise in the consumer’s world. In this way, businesses can efficiently gain invaluable insights into behavioral and attitudinal changes.

Large business customers are a different challenge, and they may seem uninterested in any topic beyond pricing. However, businesses badly need supplier innovation and now may actually be a better time than usual for real strategic dialogue. Such dialogue should entail multi-functional joint team projects, led by senior managers on both sides, with concrete goals and deadlines for co-discovery and pursuit of major new business initiatives of mutual benefit. In this environment it may make sense to experiment with very different terms, such as greatly expanded sharing of risk and accountability.

Based on such deep engagement with customers, and correspondingly careful analysis of other key players in the chain – intermediaries, competitors, regulators – a business should then creatively reinvent its value delivery strategy. What new or greatly improved value propositions should the business deliver, in what new innovative ways?

Conclusion

The deep recession is causing important, in some cases lasting, changes in behaviors, priorities, and capabilities of key players in most markets. Those changes present major opportunities to innovatively generate new growth, for businesses willing to stand up and invest in creatively discovering and then aggressively acting on those opportunities.

Capitalizing on such opportunities will require developing innovative new value propositions and/or delivering them in innovative new ways. Such innovation contrasts to either: hiding below decks, doing little more than slashing away indiscriminately at costs; or blindly betting on last year’s unchanged and unexamined strategy.

Finally, identifying and developing these crucial value-delivery innovations requires first exploring markets in search of forward-looking insights – what new experiences customers will likely find valuable, not what they valued before the downturn.

REFERENCES

1. Clark, D., WS Journal, Nvidia: Searching for the Soul of the New PC, 1/27/09

2. Tabuchi, H., NY Times, When Consumers Cut Back: A Lesson from Japan, 2/21/09

3. Kupetz, A.H., The Future for Less, pg 2, Emerald Books, 2008

4. Ibid, pg 7

5. Sanger, D., NY Times, Japanese Cars Stronger in Weak U.S. Economy, 9/4/91

6. TireBusiness.com, Yokohama to Build Car Tire Plant in Russia, 1/17/09

7. Holthaus, D., Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati.com), Kao to hire 30 in city, 1/27/09

8. Rumelt, R.P., McK Quarterly, Strategy in a Structural Break, 1/09

9. Nicholas, T., McK Quarterly, Innovation Lessons from the 1930s, 12/08

10. Bryant L., Farrell D., McK Quarterly, Leading through Uncertainty, 12/08

11. Vance, A., NY Times, Travel Goes the Way of the Dodo at Cisco, 2/5/09

12. Paul, F., CNNmoney.com, LG eyes higher market share even if revenue falls, 1/7/09

13. Baveja S., Ellis S., Rigby D., Harvard Mgmt Update, Taking Advantage of Downturn, 3/1/08

14. Dobbs R.F., Karakolev T., Malige F., McK Quarterly, Learning to Love Recessions, 2002